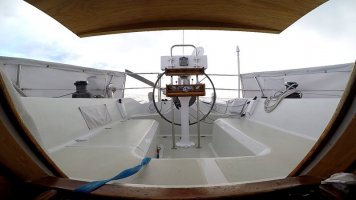

Retired from newspapers and television, currently sailing Thelonious II, a 1984 Ericson 381.

2017 breadcrumb trail here. Click on the day icons for log entries.

I spent more than a year outfitting and preparing the 1984 E38 for this solo sail from LA to Oahu and return. Upgrades included new standing rigging (partial), running rigging...

You do not have permission to view the full content of this entry.

Log in or register now.