VIDEO: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news...mwalt-is-finally-at-sea-a-lot-is-on-the-line/

The Captain is named James Kirk, and the beast sports a rail gun and almost comic-book futuristic lines.

Is it seaworthy? Is it ugly as hell, or will that inspire fear, or is there some kind of beauty in form-follows-function?

MORE ON the stability issue:

Instability Questions About Zumwalt Destroyer Are Nothing New

By Christopher P. Cavas 5:29 p.m. EST December 8, 2015

WASHINGTON — The advanced destroyer Zumwalt (DDG 1000) is scheduled to put to sea next week to begin a series of sea trials. It will be the first time the 610-foot-long ship meets the ocean, the culmination of concept and design work that began in the 1990s.

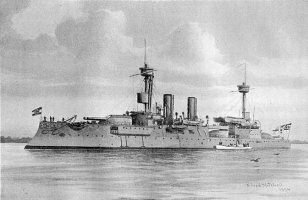

The Zumwalt and her two sister ships are built with a tumblehome hull, where the sides slope inward rather than outward or at a straight vertical as in most ship designs. The configuration, part of the ship’s low-cross section or stealth characteristics, is reminiscent of some designs of more than a century ago, but the DDG 1000 takes tumblehome to a new extreme. Essentially, no one has ever been to sea on a full-sized ship of this type.

As the ship approaches the moment when she finally meets the ocean’s rise and fall, some media stories have appeared questioning the design. There are no new questions here, however — they’ve been around since the tumblehome configuration was adopted in the late 1990s.

To give some perspective, here is a Defense News story from April 2, 2007, that — if we say so ourselves — still does a pretty good job explaining the issues and concerns, which will not likely be put to rest until the ships prove themselves at sea.

It's also worth noting that the Navy and its shipbuilders have conducted extensive modeling and testing of the concept and insist the hull form is valid.

Defense News was also among the first to present an extensive pictorial of the Zumwalt while she was under construction.

The following story was published on April 2, 2007:

Is New U.S. Destroyer Unstable?

Experts Doubt Radical Hull; Navy Says All Is Well

By CHRISTOPHER P. CAVAS

As the U.S. Navy is poised to award the first construction contracts on its new multibillion-dollar DDG 1000 Zumwalt-class destroyer, experts in and outside the Navy say the radical new hull design might be unstable.

Given just the right conditions, some say, it could even roll over.

At least eight current and former officers, naval engineers and architects and naval analysts interviewed for this article expressed concerns about the ship’s stability.

One former flag officer, asked about DDG 1000, responded by putting out his hand palm down, then flipping it over. “You mean this?” he asked.

Ken Brower, a civilian naval architect with decades of naval experience was even more blunt: “It will capsize in a following sea at the wrong speed if a wave at an appropriate wavelength hits it at an appropriate angle.”

The Navy and the lead contractors, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics, disagree. Officials from both contractors deferred to the Navy when asked about the design.

Navy leaders say the ship is stable and that they continue to test and refine the design.

“We feel very confident in the hull form,” said Allison Stiller, the deputy assistant secretary of the Navy for ship programs. “We’ve done all the modeling and testing to convince us that this is a great hull form.”

Nothing like the Zumwalt has ever been built. The 14,500-ton ship’s flat, inward-sloping sides and superstructure rise in pyramidal fashion in a form called tumblehome. Its long, angular “wave-piercing” bow lacks the rising, flared profile of most ships, and is intended to slice through waves as much as ride over them. The ship’s topsides are streamlined and free of clutter, and even the two 155mm guns disappear into their own angular housings.

The ship’s form was conceived in the mid-1990s as the ultimate stealth ship — exceptionally hard to find using conventional radars and search systems. Seagoing qualities were deliberately sacrificed, critics say, to create the most invisible surface warship ever built. To many observers, the thing just doesn’t look like a boat.

Navy officials and engineers insist the design is safe, and point to extensive testing using computers and a variety of scaled-down models that have sailed test tanks and coastal areas such as the Chesapeake Bay.

“The design is solid,” said Howard Fireman, director of the Surface Ship Design Group at Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA). “It is very mature at this point.”

The Critics

But the reality is that no full-scale ship using the Zumwalt’s configuration has ever put to sea — and that worries many veteran naval architects, engineers and surface warriors.

Norman Friedman, a naval consultant and author of a series of design histories on naval warships, said, “This thing has a very good potential for causing a lot of problems. If all the critics are right, this thing is dangerous.”

Brower explained: “The trouble is that as a ship pitches and heaves at sea, if you have tumblehome instead of flare, you have no righting energy to make the ship come back up. On the DDG 1000, with the waves coming at you from behind, when a ship pitches down, it can lose transverse stability as the stern comes out of the water — and basically roll over.”

These concerns have persisted for more than a decade, said one retired senior naval engineer who, along with many interviewed for this report, spoke only on condition of anonymity.

“It’s never been to sea before, and that obviously brings in a certain amount of risk,” he said. “I think the concerns are valid.”

Another retired senior naval officer expressed concern that, with an all-new hull form, the modeling technologies used to predict at-sea performance may be flawed. “In conventional hulls, we have done more with model testing and design work. We have correlation with ships we’ve built and sent to sea. There’s a lot of confidence in designing a conventional hull.

“We have not had tumblehome wave-piercing hulls at sea. So how would the real ship motions track with the ways we have traditionally modeled ships? How accurate is it?”

Still another naval analyst said the problem is worse than that: “It is inherently unstable.”

Although top Navy officials uniformly express confidence in the DDG 1000, there is no shortage of doubters within the service.

“When you talk with officers inside the Navy, there is a lot of trepidation over this ship,” said Bob Work, a military analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a Washington think tank. “I have never really come across that many ardent proponents for the ship. There are a lot of questions about the hull form, the tactical rationale for a stealth ship that’s constantly radiating, the need for the guns.”

But the concerns from current surface warfare officers have not persuaded Navy leaders to re-evaluate their position, he said.

From the Beginning

Doubts about the radical hull form emerged as soon as the shape was revealed in the competitive stage for what was first called DD-21, then DD(X). Both bidding teams — one led by Northrop Grumman, the other by General Dynamics — presented virtually identical tumblehome designs, as dictated by the Navy’s stealth requirements. Public discussion of the shape largely ended when the Northrop team was picked.

The Navy expects to award construction contracts for the first two ships in May to Northrop and General Dynamics — at a planned price of $3.3 billion each. Five more are planned, far fewer than the 32 once envisioned.

Ten major technology areas, including the hull, are part of the DDG 1000 development project. In expressing their confidence in the design, Navy officials said that recent meetings and reviews have concentrated on other technology areas and not addressed any concerns with the ship’s configuration.

Concerns over the hull go beyond the DDG 1000 class. The same hull form is the preferred option for a new class of missile cruisers, dubbed CG(X). The first of a planned 19 is to be ordered in 2011. The Navy is analyzing potential alternative designs now for the cruiser, which is to carry a heavier, more powerful radar and more missiles than the Zumwalt.

The prospect of a new cruiser has reignited a debate over the need for stealth itself.

“There’s no requirement for stealth,” said a retired senior line officer. “If you’re operating a million-watt radar, the question might be: Why invest in this hull in the first place? And why suffer the peril of an inherently instable hull form?”

The naval analyst scoffed at the stealth requirement. “They’ve gone to enormous lengths in order to be stealthy. And there are serious problems with that. It’s not clear that that’s going to work,” he said. “Stealth was BS to start with and is still BS.”

Critics point out that even if a stealth design is initially successful, some form of counter inevitably will be found.

“They’re not invulnerable, not undetectable,” Brower said. “In a quasi-peacetime environment, they can be detected by anyone with a Piper Cub and a pair of binoculars and a Fuzz Buster.”

The Damage-Control Problem

“I’m sure the people involved in this have been just brilliant about it and I’m being cynical,” said the naval analyst. “I could be wrong. But I’ve got to tell you, you take underwater damage with a hull like that and bad things will happen.”

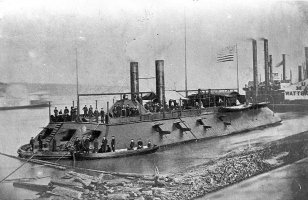

The senior surface warfare officer noted numerous discussions among other surface warfare officers about the somewhat dismal history of tumblehome ships.

The shape was popular among French naval designers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and a number of French and Russian battleships — short and fat, without any wave-piercing characteristics — were put into service. But several Russian battleships sank after being damaged by gunfire from Japanese ships in 1904 at the Battle of Tsushima, and a French battleship sank in 90 seconds after hitting a mine in World War I. All sank with serious loss of life. Both the French and Russians eventually dropped the hull form.

“The Navy has tended almost subconsciously to believe that they might not get hit,” he said. “But getting hit there is just real bad. You have to figure that some of the ships are going to take hits.”

The Zumwalt’s designers have developed a new automated fire-fighting system, a critical need in a ship with a crew of only 125 sailors. But fighting floods is more difficult without muscle power, and that worries surface officers.

Moreover, the naval analyst said, with automated damage control, “a lot depends on how your software is written. That means if your stability goes wrong at the wrong time and you find out you’ve got a software problem, you begin to submerge.”

“The Navy would say it has tested the software thoroughly and knows exactly what it is. But I personally would not like to be in that position,” he said. “It may well be that the ship will have perfectly sufficient stability most of the time. But you have to worry about conditions where software hasn’t been written correctly. People who run ships are not used to having software save them.”

More Testing?

“Some people have argued for years that you should have incrementally taken the propulsion, the gun, etc., and put these into later iterations of [DDG 51 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers] to get a better understanding of how they operate,” said the retired senior line officer. “You take that time and put it together in the CG(X), and that’s where you put together all the technologies.”

And the Navy shouldn’t base CG(X) on the Zumwalt hull “until we get some experience with DDG 1000, or get a larger model where we can verify the performance of the hull,” he said.

Other professionals would prefer to see the hull validated by an independent study group before the Navy commits to building ships.

But he admitted that there is a crucial problem with his idea.

“Frankly, the people best qualified to do it are the people already involved in the design and testing of the hull,” he said. “We’re in an area where we’ve never built a ship like this.”

There’s another element that may be at work in criticism of the ship’s design: prejudice against an unfamiliar hull form.

“There are some people who just don’t like DDG 1000,” the senior surface warfare officer said. “We’ve been assured by the senior folks that there is no problem.”

Yet others say the concern goes deeper.

“I don’t think it’s prejudice. I think there’s concern,” said the retired senior naval officer.

The Navy Responds

Those concerns are unwarranted, the Navy insists.

“A one-twentieth-scale, 30-foot scale model is undergoing testing,” said Capt. James Syring, program manager for DDG 1000. “We’ve put it though various sea states to find how the ship handles in regular seas. We’ve taken it up through Sea State Eight and even Sea State Nine [hurricane-force seas and winds] in some cases to understand the hull. All the tests are successfully confirming the tank testing and design analysis we’ve done.

“We can operate safely in Sea State Seven and Eight,” Syring said. “Unequivocally.”

Extreme conditions are dangerous for any ship, the official said.

“To say [the ship is] inherently unstable in certain sea states, there are lots of caveats to that,” Syring said.

Syring and Fireman, NAVSEA’s ship design director, did say their engineers were looking closely at “a set of very unique conditions.”

“What I’m trying to find out is what speeds do we want to avoid in those sea states,” Syring said. “We’re seeking to understand and quantify through our testing program the performance characteristics of the ship at extremely high sea states and heading position.”

Syring and Fireman bristled at suggestions the tumblehome hull would be in danger should the ship lose power or control in high seas.

“If the ship were to go dead in the water in those high sea states, the bow points into the sea and you can ride there all day because of the nature of the hull form,” Syring said. Suggestions that the ship would capsize are “not true.”

Syring addressed claims that the ship was in danger in quartering seas — waves that come at the ship from behind — by saying: “There is a wide range of safe seas on a quartering heading in Sea State Eight.”

The retired senior naval engineer agreed the Navy testing would take into account severe sea states.

“The standard Navy requirement for stability in ships is a 100-knot wind,” he said. “They’ve modeled Hurricane Camille [a Category Five storm of 1969] and they run it through that.”

“There are some sea states and conditions where you just can’t do anything you want,” said the retired senior naval officer. “A course or speed change can make all the difference in how the ship rides.”

All ships may face dangerous conditions, he said.

“To expect that this ship could go on any heading on any bearing in any condition is not reasonable to assume.”

The Navy has built scale models to test the DDG 1000 design, including a 150-foot quarter-scale steel hull that was “extraordinarily stable,” said one industry source.

The industry source said that throughout the design process, “decisions about systems to leave or replace, [changes in] weight and displacement were a continuing consideration. Whatever they shifted or removed did not affect the stability of the hull form.”

NAVSEA spokesmen said the service already has an independent board to review its designs: the Naval Technical Authority, which has determined DDG 1000 is safe.

Even among many critics, there are those familiar with the Navy team leading the DDG 1000 effort who don’t doubt the sincerity of the Navy’s engineers.

“The very best people have been working on this thing,” said the retired senior naval officer. “If they thought there was a serious flaw, they would stop it.”

But he still harbors doubts. “It all comes down to engineering and science,” he said. “I have no doubt they’ve crunched the numbers as accurately as they can. But will the actual ship follow the models? “

“These retired folks don’t have the data that I have,” Syring said. “The last thing I’d be doing right now is to award ship-construction contracts if the technical people have problems.”

“The checks and balances in our system just don’t allow us to award contracts if the design is considered unsafe,” declared Fireman.

The senior surface warfare officer also supported the design team. “Those folks are genuinely interested and passionate,” he said. “We do not deliberately design ships with known flaws.”

But the doubts persist despite the Navy’s declarations of confidence in the design.

“My sense is there’s a bit of a there there,” the senior surface warfare officer said. “It might be extremely rare for the circumstances to come together, but if you’re going to stake out that this is your hull form for the future, there could be a tremendous cost, so this is worth investigating.”

One question the Navy should ask, he said, is: “Why does this question [of doubt] persist?”

Email ccavas@defensenews.com

The Captain is named James Kirk, and the beast sports a rail gun and almost comic-book futuristic lines.

Is it seaworthy? Is it ugly as hell, or will that inspire fear, or is there some kind of beauty in form-follows-function?

MORE ON the stability issue:

Instability Questions About Zumwalt Destroyer Are Nothing New

By Christopher P. Cavas 5:29 p.m. EST December 8, 2015

WASHINGTON — The advanced destroyer Zumwalt (DDG 1000) is scheduled to put to sea next week to begin a series of sea trials. It will be the first time the 610-foot-long ship meets the ocean, the culmination of concept and design work that began in the 1990s.

The Zumwalt and her two sister ships are built with a tumblehome hull, where the sides slope inward rather than outward or at a straight vertical as in most ship designs. The configuration, part of the ship’s low-cross section or stealth characteristics, is reminiscent of some designs of more than a century ago, but the DDG 1000 takes tumblehome to a new extreme. Essentially, no one has ever been to sea on a full-sized ship of this type.

As the ship approaches the moment when she finally meets the ocean’s rise and fall, some media stories have appeared questioning the design. There are no new questions here, however — they’ve been around since the tumblehome configuration was adopted in the late 1990s.

To give some perspective, here is a Defense News story from April 2, 2007, that — if we say so ourselves — still does a pretty good job explaining the issues and concerns, which will not likely be put to rest until the ships prove themselves at sea.

It's also worth noting that the Navy and its shipbuilders have conducted extensive modeling and testing of the concept and insist the hull form is valid.

Defense News was also among the first to present an extensive pictorial of the Zumwalt while she was under construction.

The following story was published on April 2, 2007:

Is New U.S. Destroyer Unstable?

Experts Doubt Radical Hull; Navy Says All Is Well

By CHRISTOPHER P. CAVAS

As the U.S. Navy is poised to award the first construction contracts on its new multibillion-dollar DDG 1000 Zumwalt-class destroyer, experts in and outside the Navy say the radical new hull design might be unstable.

Given just the right conditions, some say, it could even roll over.

At least eight current and former officers, naval engineers and architects and naval analysts interviewed for this article expressed concerns about the ship’s stability.

One former flag officer, asked about DDG 1000, responded by putting out his hand palm down, then flipping it over. “You mean this?” he asked.

Ken Brower, a civilian naval architect with decades of naval experience was even more blunt: “It will capsize in a following sea at the wrong speed if a wave at an appropriate wavelength hits it at an appropriate angle.”

The Navy and the lead contractors, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics, disagree. Officials from both contractors deferred to the Navy when asked about the design.

Navy leaders say the ship is stable and that they continue to test and refine the design.

“We feel very confident in the hull form,” said Allison Stiller, the deputy assistant secretary of the Navy for ship programs. “We’ve done all the modeling and testing to convince us that this is a great hull form.”

Nothing like the Zumwalt has ever been built. The 14,500-ton ship’s flat, inward-sloping sides and superstructure rise in pyramidal fashion in a form called tumblehome. Its long, angular “wave-piercing” bow lacks the rising, flared profile of most ships, and is intended to slice through waves as much as ride over them. The ship’s topsides are streamlined and free of clutter, and even the two 155mm guns disappear into their own angular housings.

The ship’s form was conceived in the mid-1990s as the ultimate stealth ship — exceptionally hard to find using conventional radars and search systems. Seagoing qualities were deliberately sacrificed, critics say, to create the most invisible surface warship ever built. To many observers, the thing just doesn’t look like a boat.

Navy officials and engineers insist the design is safe, and point to extensive testing using computers and a variety of scaled-down models that have sailed test tanks and coastal areas such as the Chesapeake Bay.

“The design is solid,” said Howard Fireman, director of the Surface Ship Design Group at Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA). “It is very mature at this point.”

The Critics

But the reality is that no full-scale ship using the Zumwalt’s configuration has ever put to sea — and that worries many veteran naval architects, engineers and surface warriors.

Norman Friedman, a naval consultant and author of a series of design histories on naval warships, said, “This thing has a very good potential for causing a lot of problems. If all the critics are right, this thing is dangerous.”

Brower explained: “The trouble is that as a ship pitches and heaves at sea, if you have tumblehome instead of flare, you have no righting energy to make the ship come back up. On the DDG 1000, with the waves coming at you from behind, when a ship pitches down, it can lose transverse stability as the stern comes out of the water — and basically roll over.”

These concerns have persisted for more than a decade, said one retired senior naval engineer who, along with many interviewed for this report, spoke only on condition of anonymity.

“It’s never been to sea before, and that obviously brings in a certain amount of risk,” he said. “I think the concerns are valid.”

Another retired senior naval officer expressed concern that, with an all-new hull form, the modeling technologies used to predict at-sea performance may be flawed. “In conventional hulls, we have done more with model testing and design work. We have correlation with ships we’ve built and sent to sea. There’s a lot of confidence in designing a conventional hull.

“We have not had tumblehome wave-piercing hulls at sea. So how would the real ship motions track with the ways we have traditionally modeled ships? How accurate is it?”

Still another naval analyst said the problem is worse than that: “It is inherently unstable.”

Although top Navy officials uniformly express confidence in the DDG 1000, there is no shortage of doubters within the service.

“When you talk with officers inside the Navy, there is a lot of trepidation over this ship,” said Bob Work, a military analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a Washington think tank. “I have never really come across that many ardent proponents for the ship. There are a lot of questions about the hull form, the tactical rationale for a stealth ship that’s constantly radiating, the need for the guns.”

But the concerns from current surface warfare officers have not persuaded Navy leaders to re-evaluate their position, he said.

From the Beginning

Doubts about the radical hull form emerged as soon as the shape was revealed in the competitive stage for what was first called DD-21, then DD(X). Both bidding teams — one led by Northrop Grumman, the other by General Dynamics — presented virtually identical tumblehome designs, as dictated by the Navy’s stealth requirements. Public discussion of the shape largely ended when the Northrop team was picked.

The Navy expects to award construction contracts for the first two ships in May to Northrop and General Dynamics — at a planned price of $3.3 billion each. Five more are planned, far fewer than the 32 once envisioned.

Ten major technology areas, including the hull, are part of the DDG 1000 development project. In expressing their confidence in the design, Navy officials said that recent meetings and reviews have concentrated on other technology areas and not addressed any concerns with the ship’s configuration.

Concerns over the hull go beyond the DDG 1000 class. The same hull form is the preferred option for a new class of missile cruisers, dubbed CG(X). The first of a planned 19 is to be ordered in 2011. The Navy is analyzing potential alternative designs now for the cruiser, which is to carry a heavier, more powerful radar and more missiles than the Zumwalt.

The prospect of a new cruiser has reignited a debate over the need for stealth itself.

“There’s no requirement for stealth,” said a retired senior line officer. “If you’re operating a million-watt radar, the question might be: Why invest in this hull in the first place? And why suffer the peril of an inherently instable hull form?”

The naval analyst scoffed at the stealth requirement. “They’ve gone to enormous lengths in order to be stealthy. And there are serious problems with that. It’s not clear that that’s going to work,” he said. “Stealth was BS to start with and is still BS.”

Critics point out that even if a stealth design is initially successful, some form of counter inevitably will be found.

“They’re not invulnerable, not undetectable,” Brower said. “In a quasi-peacetime environment, they can be detected by anyone with a Piper Cub and a pair of binoculars and a Fuzz Buster.”

The Damage-Control Problem

“I’m sure the people involved in this have been just brilliant about it and I’m being cynical,” said the naval analyst. “I could be wrong. But I’ve got to tell you, you take underwater damage with a hull like that and bad things will happen.”

The senior surface warfare officer noted numerous discussions among other surface warfare officers about the somewhat dismal history of tumblehome ships.

The shape was popular among French naval designers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and a number of French and Russian battleships — short and fat, without any wave-piercing characteristics — were put into service. But several Russian battleships sank after being damaged by gunfire from Japanese ships in 1904 at the Battle of Tsushima, and a French battleship sank in 90 seconds after hitting a mine in World War I. All sank with serious loss of life. Both the French and Russians eventually dropped the hull form.

“The Navy has tended almost subconsciously to believe that they might not get hit,” he said. “But getting hit there is just real bad. You have to figure that some of the ships are going to take hits.”

The Zumwalt’s designers have developed a new automated fire-fighting system, a critical need in a ship with a crew of only 125 sailors. But fighting floods is more difficult without muscle power, and that worries surface officers.

Moreover, the naval analyst said, with automated damage control, “a lot depends on how your software is written. That means if your stability goes wrong at the wrong time and you find out you’ve got a software problem, you begin to submerge.”

“The Navy would say it has tested the software thoroughly and knows exactly what it is. But I personally would not like to be in that position,” he said. “It may well be that the ship will have perfectly sufficient stability most of the time. But you have to worry about conditions where software hasn’t been written correctly. People who run ships are not used to having software save them.”

More Testing?

“Some people have argued for years that you should have incrementally taken the propulsion, the gun, etc., and put these into later iterations of [DDG 51 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers] to get a better understanding of how they operate,” said the retired senior line officer. “You take that time and put it together in the CG(X), and that’s where you put together all the technologies.”

And the Navy shouldn’t base CG(X) on the Zumwalt hull “until we get some experience with DDG 1000, or get a larger model where we can verify the performance of the hull,” he said.

Other professionals would prefer to see the hull validated by an independent study group before the Navy commits to building ships.

But he admitted that there is a crucial problem with his idea.

“Frankly, the people best qualified to do it are the people already involved in the design and testing of the hull,” he said. “We’re in an area where we’ve never built a ship like this.”

There’s another element that may be at work in criticism of the ship’s design: prejudice against an unfamiliar hull form.

“There are some people who just don’t like DDG 1000,” the senior surface warfare officer said. “We’ve been assured by the senior folks that there is no problem.”

Yet others say the concern goes deeper.

“I don’t think it’s prejudice. I think there’s concern,” said the retired senior naval officer.

The Navy Responds

Those concerns are unwarranted, the Navy insists.

“A one-twentieth-scale, 30-foot scale model is undergoing testing,” said Capt. James Syring, program manager for DDG 1000. “We’ve put it though various sea states to find how the ship handles in regular seas. We’ve taken it up through Sea State Eight and even Sea State Nine [hurricane-force seas and winds] in some cases to understand the hull. All the tests are successfully confirming the tank testing and design analysis we’ve done.

“We can operate safely in Sea State Seven and Eight,” Syring said. “Unequivocally.”

Extreme conditions are dangerous for any ship, the official said.

“To say [the ship is] inherently unstable in certain sea states, there are lots of caveats to that,” Syring said.

Syring and Fireman, NAVSEA’s ship design director, did say their engineers were looking closely at “a set of very unique conditions.”

“What I’m trying to find out is what speeds do we want to avoid in those sea states,” Syring said. “We’re seeking to understand and quantify through our testing program the performance characteristics of the ship at extremely high sea states and heading position.”

Syring and Fireman bristled at suggestions the tumblehome hull would be in danger should the ship lose power or control in high seas.

“If the ship were to go dead in the water in those high sea states, the bow points into the sea and you can ride there all day because of the nature of the hull form,” Syring said. Suggestions that the ship would capsize are “not true.”

Syring addressed claims that the ship was in danger in quartering seas — waves that come at the ship from behind — by saying: “There is a wide range of safe seas on a quartering heading in Sea State Eight.”

The retired senior naval engineer agreed the Navy testing would take into account severe sea states.

“The standard Navy requirement for stability in ships is a 100-knot wind,” he said. “They’ve modeled Hurricane Camille [a Category Five storm of 1969] and they run it through that.”

“There are some sea states and conditions where you just can’t do anything you want,” said the retired senior naval officer. “A course or speed change can make all the difference in how the ship rides.”

All ships may face dangerous conditions, he said.

“To expect that this ship could go on any heading on any bearing in any condition is not reasonable to assume.”

The Navy has built scale models to test the DDG 1000 design, including a 150-foot quarter-scale steel hull that was “extraordinarily stable,” said one industry source.

The industry source said that throughout the design process, “decisions about systems to leave or replace, [changes in] weight and displacement were a continuing consideration. Whatever they shifted or removed did not affect the stability of the hull form.”

NAVSEA spokesmen said the service already has an independent board to review its designs: the Naval Technical Authority, which has determined DDG 1000 is safe.

Even among many critics, there are those familiar with the Navy team leading the DDG 1000 effort who don’t doubt the sincerity of the Navy’s engineers.

“The very best people have been working on this thing,” said the retired senior naval officer. “If they thought there was a serious flaw, they would stop it.”

But he still harbors doubts. “It all comes down to engineering and science,” he said. “I have no doubt they’ve crunched the numbers as accurately as they can. But will the actual ship follow the models? “

“These retired folks don’t have the data that I have,” Syring said. “The last thing I’d be doing right now is to award ship-construction contracts if the technical people have problems.”

“The checks and balances in our system just don’t allow us to award contracts if the design is considered unsafe,” declared Fireman.

The senior surface warfare officer also supported the design team. “Those folks are genuinely interested and passionate,” he said. “We do not deliberately design ships with known flaws.”

But the doubts persist despite the Navy’s declarations of confidence in the design.

“My sense is there’s a bit of a there there,” the senior surface warfare officer said. “It might be extremely rare for the circumstances to come together, but if you’re going to stake out that this is your hull form for the future, there could be a tremendous cost, so this is worth investigating.”

One question the Navy should ask, he said, is: “Why does this question [of doubt] persist?”

Email ccavas@defensenews.com

Last edited: