After a week of profound serenity, monotony began settling in: the same sapphire-blue ocean; a steady 15-18 knot wind driving gentle, predictable waves; night after night of luminous stars, and a Milky Way I’d never seen without obstruction, or with such brilliance. The days grew warmer, and I began finding ways to pass the time. I stared aft from the cabin often, studying carefully the back-and-forth movement of the rudder head, which protrudes through the cockpit sole on the 35-II...

-

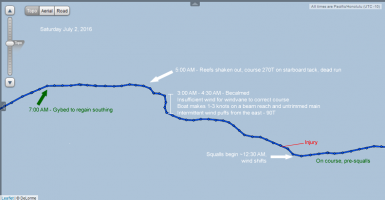

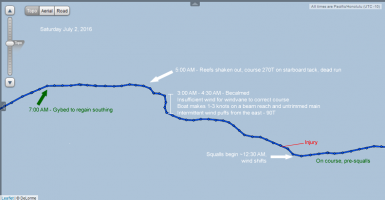

7-2-map.png

218.4 KB · Views: 706

-

7-2-video.png

859.4 KB · Views: 319

-

7-4-Squall-Passing.png

747.5 KB · Views: 320

-

gloomy-seas.png

2.1 MB · Views: 332

-

sentry-helmsman.png

1.4 MB · Views: 325